In all real estate transactions, money changes hands. A price is agreed between buyer and seller, contracts arranged and the transaction proceeds.

But it’s important to consider the source of the money (“capital”) for the deal. Will the purchase price be paid with capital provided by the buyer alone (“buyer’s equity” or just “equity”)? Or will the buyer borrow some of the money, seeking some form of loan or mortgage (“debt”) to fund part of the transaction—either as the buyer doesn’t have enough equity to purchase outright or, for a variety of other reasons, doesn’t wish to use all of his equity to fund the purchase?

In reality, almost without exception, all major residential and commercial properties will be acquired using a combination of equity and debt.

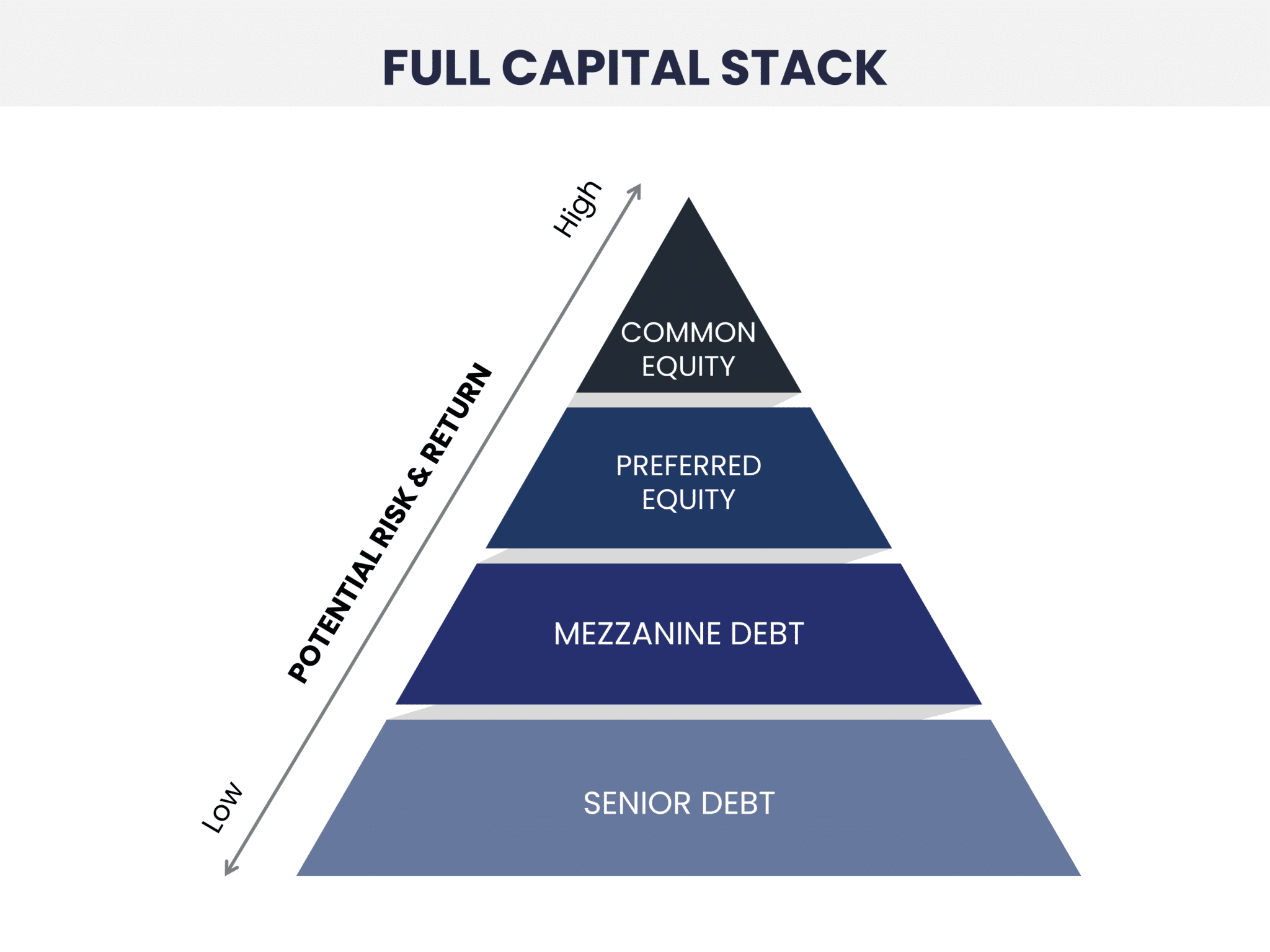

However, not all capital (equity and/or debt) is the same and capital can be broken down into several “layers” or “sub-divisons”, with different types of equity and debt available for use by investors. Some of these layers of capital are known as “common equity” and “preferred equity” and “mezzanine” and “senior debt” and will be looked at more closely later.

This mixture of capital (probably a mixture of equity and debt) in any real estate transaction is very important and is often known as a “capital stack”. That is, not only are the various sources of capital identified and recorded. but they are “stacked” in layers representing the different types of capital being employed in a deal. The use of layers helps those parties involved in the transaction understand both the sources of capital, but also where priorities for repayment of debt and distribution of profits lie.

In short, a capital stack represents the underlying financial structure of a commercial real estate deal. It is one of the most important concepts for investors to use in evaluating risks associated with real estate and projected rates of return.

By having a complete understanding of a capital stack, investors can help protect their investments and achieve their desired gains by identifying areas of insufficient gains or, conversely, where the greatest risks lie. The capital stack is amongst the most valuable techniques used in evaluating a potential investment in a commercial real estate deal, as it enables investors to know who gets paid/repaid, at what point in the investment cycle, and how much risk each party carries.

So, let’s have a closer look at how a capital stack works in terms of assessing investments, risks and rewards.

Further explanation of a capital stack

Layers and priorities within a capital stack

A capital stack typically comprises four layers or sections representing capital involved when an investor purchases and operates a commercial real estate investment. These are arranged in the following order, and are divided into equity and debt (see Figure 1 below):

- common equity

- preferred equity

- mezzanine debt

- senior debt.

All income and profits generated by the property will be outlined in the stack and, importantly, will show the order of distribution of such funds to each party providing the capital. The capital stack also defines which party has the first right to foreclose on the asset as collateral in the event the equity owner defaults on the mortgage.

Senior debt, although typically positioned at the bottom of the capital stack, repayment of this debt has the highest priority, meaning that senior debt lenders will be the first to be repaid in the event of any default.

Although common equity is usually positioned in first place or at the top of the stack, it has the lowest priority, meaning that common equity lenders are paid last after the holders of the other stack components have been paid or repaid.

Despite the lower priority for payment, it should be noted that the higher placed positions in a capital stack, typically, earn higher returns as a result of their higher levels of risk.

A simple example of a capital stack is below:

Let’s say a property is purchased for $5,000,000.

The down payment (equity) is to be 20% and a mortgage or loan (debt) is obtained for the remaining 80%.

In this case the capital stack would be:

| Type of capital | Amount | % of total capital |

|---|---|---|

| Equity (down payment) | $1,000,000 | 20% |

| Debt (mortgage/loan) | $4,000,000 | 80% |

| Total | $5,000,000 | 100% |

In the event the property is sold for more than $5,000,000, either as a result of a planned sale to lock-in profits or due to a default, from the sales proceeds the lender of the debt

(usually a bank) is paid first and the equity holders paid later after debt obligations have been met.

However, in a situation where the sales proceeds, for some reason, are less than $5,000,000, the debt provider will still be paid first, but the equity holder’s position may be zero. In such a case, the lender may seek to recover its entire debt by pursuing other collateral originally provided by the borrower, which may include a personal guarantee or other assets.

Order of repayment priority within a capital stack

As mentioned and shown above, in a capital stack, the four types of capital typically deployed in real estate transactions are listed from the lowest priority to highest priority.

It goes without saying, therefore, that investors who are more comfortable with higher levels of risk and wish to secure a higher return will want to focus on being participants in the positions in the upper part of the capital stack (the common equity and preferred equity positions).

On the other hand, investors who are more risk averse will most likely want to participate in a position in the lower portion of the stack (mezzanine debt and senior debt), which are more secure in their ability to be repaid but, as a result, offer lower returns.

When reviewing the capital stack in any real estate transaction, some of the key issues to be aware of include the following:

- capital stacks show how different capital types are prioritized by seniority, with the most senior on the bottom and the least senior on the top;

- equity positions for both common and preferred equity are listed first, with debt positions below;

- if a property doesn’t generate enough annual rental income or, in the event of a sale, enough proceeds to pay or repay all investors or debtors, the property’s income or sales proceeds will be distributed to the providers of capital, moving from the bottom layer upward. Such distribution starts by addressing the obligation to the senior debt holders, and then to mezzanine debt providers. Any funds left over after such distribution will then flow up the capital stack to the preferred equity and, finally, the common equity positions;

- should the property go into default for any reason, claims to assets and repayment of capital are dealt with in order of seniority. The capital holders positioned in the lower layers of the stack having greater rights/claims to repayment and foreclosure rights superior to those higher up in the stack;

- generally higher risk capital (equity) sits at the top of the capital stack, with lower risk occupying the lower places; the most secure or lowest risk capital being at the bottom. Conversely, capital seeking higher potential returns potential will occupy the places at the top of the capital stack, whilst those capital providers lower in the stack seeing lower but more secure returns;

- the various components of a capital stack are the framework of the financing for any type of real estate transaction. Selecting the mix of the right capital stack components can make or break a project as they drive the financing and profitability of a project.

Over-leveraging a project is a common risk for many real estate investors; that is, they increase the debt portion of their capital stack to magnify their anticipated returns based on the equity portion. Whilst this does reduce the amount of equity required relative to projected profits, it can also expose a project to excessive risks of default or foreclosure in the event that senior or mezzanine debt cannot be serviced.

On the other hand, under-leveraging a project by not optimizing the amount of debt can also mean foregoing some of the anticipated profits.

Finding the optimal balance in the capital structure between debt and equity and the integration of the right levels of preferred equity and mezzanine debt can only be achieved with years of real estate investment experience and solid underwriting knowledge.

The four layers of capital in a capital stack

Typically, capital (both equity and debt) in a capital stack can be grouped into one of four categories: namely, common equity, preferred equity, mezzanine debt and senior debt.

Let’s have a closer look at each of these four components:

Senior Debt:

- holds priority over all other positions in the capital stack; that is, providers of senior debt are to be paid before any other investor is paid a return on its investment (see Figure 2. below);

- is usually provided by a bank or some other debt holder who has the highest claim on the underlying asset. This is the most secure (or least risky) position to hold in the capital stack because, if the borrower fails to repay the loan payments, the senior debt provider can take over the property ownership through a foreclosure action and sell the property to recover the amount owed.

Such senior debt providers will look closely at the loan-to-value ratio (“LTV”) of a project which is the amount of debt on a property relative to its overall value.

If, for example, the loan has an LTV of 65%, there is more flexibility and margin for error than in a project where the LTV is 85%.

That is, the lender would prefer owning the property if there was a default at 65% of its market value rather than at 85%, as clearly there will be more chance to recover the capital loaned in the latter situation; - typically comprises 75% of the total project cost, although this can vary depending on several factors such as the risk profile of a project, the stage of the market cycle, and the creditworthiness of the borrower;

- is the best secured position in the capital stack because it retains the property itself as collateral, but the trade-off for such security is that the senior debt provider typically receives the lowest return of any other position in the stack.

Mezzanine Debt:

- will be serviced after all operating expenses and senior debt payments have been made. Therefore, mezzanine ranks behind senior debt in order of payment priority and is usually in second position in the capital stack (see Figure 3. below). Because of such secondary nature and slightly higher risk, mezzanine debt providers will expect a higher rate of return than senior debt;

Preferred Equity:

- has evolved over the last decade or so into having a slightly different meaning than previously. In the past, the term preferred equity was used to describe capital which had superior repayment rights to common equity although its application in capital transactions was similar.

Nowadays, preferred equity has changed to function more like subordinate debt and receive a fixed return excluding any share of profits, although having enhanced rights to take over a project in the event of default.

One key catalyst for the evolution was the fact that mezzanine lenders previously had stronger rights than expected which, in turn, complicated recovery efforts in respect of the property of senior debt or other lien holders in the event borrowers defaulted.

Over time, lenders increasingly prohibited the use of second position loans, including mezzanine debt and, so, preferred equity was restructured to fill the gap in the capital stack. However, such preferred equity was no longer called or made to look like debt,

although its function is as close to debt as first mortgage lender requirements allow (see Figure 4. below);

Common Equity:

- is provided by the sponsor or operator and their investor partners and is the riskiest yet potentially most profitable portion of the capital stack (see Figure 5. below). In almost every real estate transaction, lenders require the sponsors or developers to invest some of their own money into the project via common equity;

- holders get paid after all other participants in the capital stack (both debt and preferred equity providers) have received their agreed-upon returns, meaning that common equity holders are last in the priority line for payment;

- holders are entitled to non-guaranteed recurring payments from the property’s cash flow after all other capital holders have been paid, usually in the form of a preferred return on their investment;

- holders participate in property cash flow distributions and, if the property does well, equity investors usually do not have a cap on their return potential.

Within the equity component of a real estate transaction, there are two primary structures to consider, namely:

Single-Tier Equity Structures with three key components

There are three different components to a Single-Tier Equity capital stack structure (see Figure 6. below). Firstly, there will be senior debt, then Class A shares and Class B shares; the way this works can be explained as follows:

- the senior debt relates to the primary loan to acquire the asset;

- Class A shares will be allocated to the limited partners and who will bring 100% of the equity required for the transaction, usually in conjunction with a variety of passive investors;

- Class B shares in the capital stack are reserved for the sponsors or those putting the deal together;

- when the property asset is sold, the senior debt is repaid first, then Class A shareholders will receive their initial capital returned in full. Finally, profits will be split in the ratio of, typically, 70% to Class A shareholders and 30% to Class B shareholders.

Dual-Tier Equity Structures with four key components

An alternative capital stack structure has four components and is often called Dual-Tier Equity structure. Again, firstly, there will be senior debt, then Class A shares Class B shares but, in this case, there will be an extra class: Class C shares.

The way this works can be explained as follows:

- the senior debt, as before, will be for the primary loan to acquire the asset;

- Class A shares will be allocated to limited partners in what is considered a preferred equity position and they will contributed some 25-35% of the equity required for the transaction;

- Class B shares will also be for the limited partners and will bring in the remaining 65-75% of the required equity, usually in conjunction with a variety of passive investors. This means that the equity is a mixture of both Class A shares or Class B shares, with the exact mix determined closer to finalization of funding;

- Class C shares are reserved for the sponsors or those putting the deal together (see Figure 7. below);

- when the property asset is sold, as with the single tier structure, the senior debt is paid back first, then Class A shareholders will have their initial capital returned in full as will Class B shareholders. Finally, profits will be split in the ratio of, typically, 70% to Class B shareholders and 30% to Class C shareholders.

- since Class A shareholders are in a preferred equity position they do not participate in the profit distribution as they are paid a higher preferred return in exchange for potential upside on the deal.

Hedging risks with Preferred Equity Positions

The preferred equity position provides the lowest risk, apart from those risks associated with senior debt, being as close to a guaranteed return as it’s possible to get in these types of investments.

If the preferred equity position does not get paid, the common equity position will not be paid either. Many institutional and other experienced investors ideally want to be in a preferred equity position to lower risks within the investment..

The capital stack is one of the most important items to be reviewed and understood prior to making any real estate investment, but there are also other considerations such as how preferred returns are structured, the meaning and impact of equity waterfalls, distribution hurdles, etc.

Why is the Capital Stack important?

The capital stack of any commercial real estate investment can be said to one of the most important concepts an investor needs to grasp when analyzing the equity and debt structure, and risk return profile of a project.

Given that investment in commercial real estate has some degree of risk, investors can utilize a capital stack to assess risk and repayment schedules and their own position in terms of eligibility for cash flows and returns, plus ascertain whether or not the investment is worth the assumed risk.

Another important aspect of a capital stack is that it provides an overview of the interests and/or future claims which every investor has in the project. This will indicate which entity has the strongest ability to take over ownership of the property in the event the borrower defaults.

The senior debt holder will have a claim in the form of collateral in the property for the amount of the loan which is owed to them and still outstanding—the principal amount including any interest payments, fees and penalties which might accrue, plus the right to repossess the property if there is a material default.

Mezzanine lenders have a right to take over the positions of equity holders in the event the borrower defaults on the mezzanine payments, although they will not take the senior debt (first mortgage) position. Actually, the mezzanine lender would become the equity holder and be required to continue payments to the senior debt lender.

Generally, equity holders do not have foreclosure rights on a property and, therefore, could potentially lose their equity completely in the event the sponsor defaults on debt repayments to a lender higher up the capital stack.

Analysis of the capital stack allows investors to determine the level of their risk associated with an investment. If there is a higher percentage of debt in the capital structure, this will mean more financing costs and, consequently, a higher risk of default by the borrower should the market situation change and the project not meet its return objectives. On the other hand, an equity-heavy capital structure is preferred as there is less chance of a borrower defaulting on a loan..

Factors which may impact risk and the potential investment upside

When analyzing specific projects, there are a variety of factors which can affect both the risks and the upside potential of any real estate investment, and these include.:

- stability of cash flows: how stable or sustainable current and projected cash flows of a project may be over the long run;

- demand and supply in the chosen market: it’s essential to analyze in detail the current and projected level of demand, as well as present competition and likely future supply in the market

- location and economic well-being: investments into, say, multi-family projects where there is likely to be sustained demand due to factors such as an attractive climate, diverse employment base, and other positive attributes which make the area desirable for employers and employees alike will invariably lead to success. On the other hand, returns may be better in markets which are still to be adequately explored or are experiencing some short-term negative factors;

- overall business strategy: can make the performance of investments differ wildly in their risk/return profiles. Having an experienced sponsor developing and executing a well-considered business plan and strategy is a very important component in mitigating risk, so that matters such as the project’s complexity, potential/current cash flow, lease-up numbers and rent rolls can help maximize the return potential;

- condition of property: if extensive, complex capital improvements are needed to bring a property up to habitable standards or there is a lengthy process to bring rentals and cash flows in line with the current market, the more profit the property forgoes whilst the improvements or changes are implemented;

When we at CPI Capital are structuring deals, we always take particular care to ensure that every real estate investment we are involved with has the most appropriate combination of common equity, preferred equity, mezzanine debt and senior debt when creating the capital stack.

We need to fully understand, each and every time, where we as investors sit in the capital stack to help assess the level of risk we and our passive investors are likely to be exposed to vis-a-via other participants in the project. As a prudent investor we will always look to see the extent to which lenders, who retain the property as collateral, are involved, and how the returns of other equity holders compare.

We hope you found this summary about capital stacks useful!

Yours sincerely,

– Ava Benesocky

CEO, Co-Founder Canadian Passive Investing

– August Biniaz

Chief Strategy Officer, Co-Founder Canadian Passive Investing

Ready to build true wealth for your family?

It all starts with passive income. Apply to join the CPI Capital Investor Club.

Search

Recommended